The film and television industry has historically been led by men, particularly in writing, directing, producing, and casting roles. As a result, many of the stories we see are shaped through a predominantly male perspective, including how female characters are written, portrayed, and understood. This influence is especially visible in how women — and particularly younger women — are sexualised on screen.

From casting decisions to camera angles, women’s bodies are frequently framed as objects of visual consumption rather than as full human subjects. Youth is prioritised, sexual availability is implied, and attractiveness is treated as narrative currency. Even today, most screenwriters, directors, and producers are men, most speaking roles go to men, and most roles written for women skew younger than their male counterparts. Even background characters — crowds, police, soldiers, scientists, experts — overwhelmingly default to men. When women do appear, especially young women, they are far more likely to be conventionally attractive, styled for visual appeal, framed through the male gaze, and sexualised regardless of relevance to the plot.

This means that the average woman on screen is not a woman at all. She is a male idea of a woman — crafted, filtered, and restricted by a male lens. When men write women, a very specific pattern emerges. Women are frequently sexualised before they are characterised, valued for desirability over competence, and framed through bodies rather than minds. Young female characters are often introduced through lingering shots, tight clothing, sexualised dialogue, and romantic subplots that exist primarily to motivate male characters. Meanwhile, male characters are allowed to age, to exist unsexualised, and to be defined by skill, intelligence, leadership, or moral complexity.

Sexualisation becomes a shortcut — a way to make women “interesting” without giving them interior lives. And once a woman is sexualised, her competence is often undermined. She may be portrayed as illogical, emotionally fragile, impulsive, dependent on male reassurance, or positioned as a distraction rather than a contributor. This pattern extends beyond sexuality into capability.

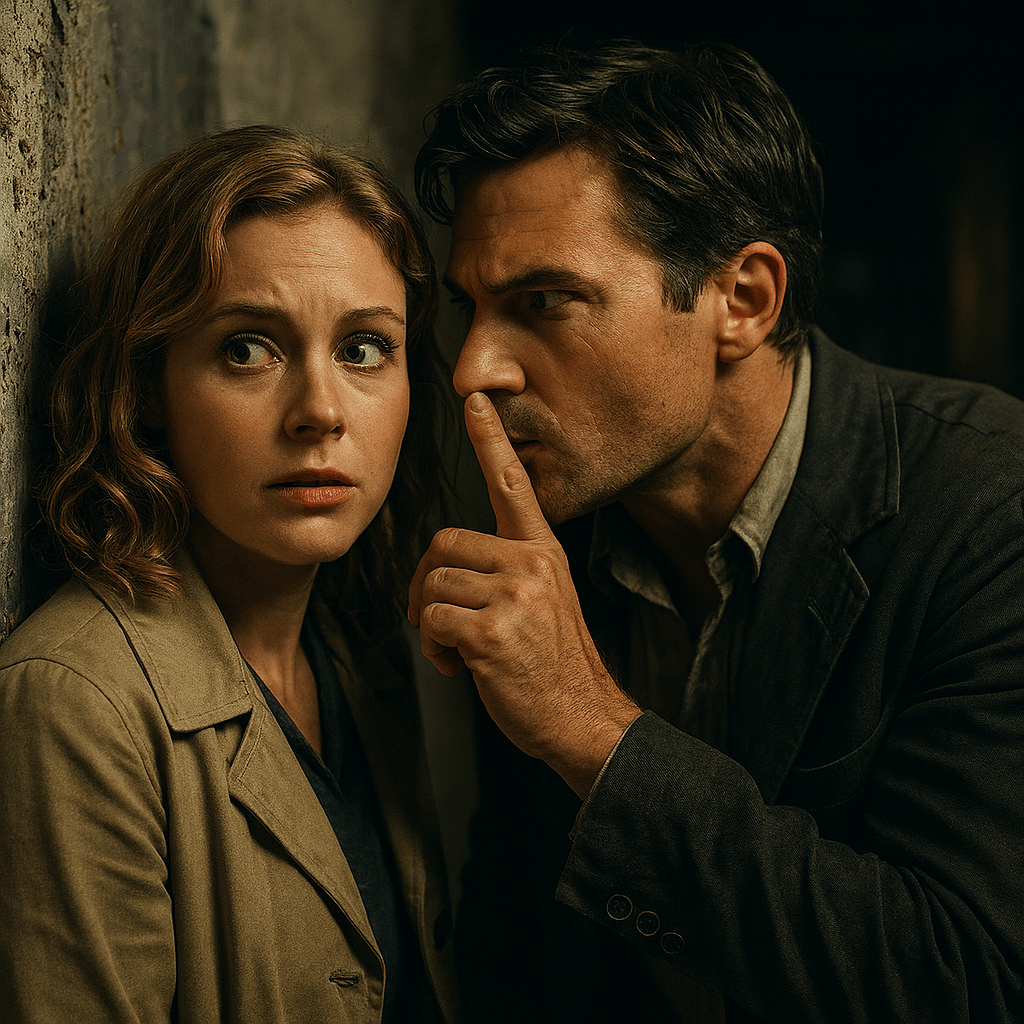

Think of how many films follow a familiar scene. The group must stay silent. The tension is high. The stakes are life and death. Everything depends on absolute quiet. And who breaks the silence? The woman. She gasps too loudly, cries, panics, trips, or screams at the wrong moment. The message is subtle but consistent: women ruin everything. This trope is so deeply embedded that audiences barely notice it anymore, yet its function is clear — to signal that women cannot be trusted in moments requiring discipline, restraint, or strategic thinking.

In reality, women are statistically more likely to remain calm under pressure, organise responses in emergencies, and take leadership roles during crises, particularly when others are vulnerable. Hollywood isn’t reflecting reality. It’s reflecting the assumptions of the men who write it.

In countless films, when danger strikes — a fire, an accident, a break-in, a medical emergency — the woman instinctively turns to a man and asks what to do, calls for help, or demands that he act. This happens even when she is more qualified, more experienced, calmer, or clearly more capable. The script demands deference. The man must lead. The woman must follow. This reinforces the idea that men are natural problem-solvers, while women exist in a state of dependency, even when the evidence contradicts it.

Another structural issue lies in dialogue. Men often write how they imagine women speak rather than how women actually speak. This results in female characters who ask unnecessary questions, slow the plot, overreact emotionally, sabotage plans, or exist primarily to be rescued, punished, or sexualised. Women become narrative devices rather than agents. Over time, these portrayals harden into “truths” that audiences accept without question.

Even when women are written as strong or competent, they are rarely allowed strength without consequence. Hollywood often responds by making her emotionally cold, hypersexualising her, humiliating her, killing her, or recasting her as the villain. Male characters are allowed contradiction. Women are allowed narrow lanes.

Even the extras tell the story. Look closely at the next film you watch and notice who fills the room, who occupies authority, and who exists as default. Men dominate the background as well as the foreground. The unspoken lesson is clear: men inhabit the world, women visit it.

When audiences consume thousands of hours of male-written female behaviour, a script is formed in which women are emotional, women panic, women are unreliable, women need saving, while men lead, men decide, and men act, shaping beliefs that are not learned through lived experience but absorbed through stories.

Most films are not windows into women’s reality. They are windows into men’s imaginations. Women on screen fail, scream, freeze, or exist to be desired not because women are like that, but because men wrote them that way. If women held equal power behind the camera, the screen would look different — women thinking clearly, women leading, women acting decisively, women existing without sexualisation as a prerequisite for relevance. We are not watching women. We are watching a version of womanhood constrained by who has historically held the pen.

Leave a comment